I recently watched Wilding, a movie about a farming couple from the Southeast of England who “rewilded” their 3,500 acre estate.

Rewilding is a concept I had not given much thought to until viewing this film, and apparently it is not without controversy among ecologists, conservationists and farmers.

The idea is to allow land to return to its “natural” state. This is talked of as taking a laissez faire approach to the land, letting it return to its naturally biodiverse origin. As the film demonstrates, it can be a bit more complicated than that, but not much.

The film follows Charlie Burrell and Isabella Tree of Knepp Castle, inspired to rewild their estate by a Dutch ecologist named Dr.

Frans Vera. Vera stood out for his heterodox view about the norm for the European landscape at the end of the Pleistocene period, otherwise known as the Ice Age.

Vera’s “wood-pasture hypothesis” argues that open pastures and wood pastures were the norm in Western Europe at the beginning of the

Holocene, with packs of wild herbivores roaming European pastures. Their grazing once kept large expanses of land free from forest cover, creating the open habitats that supported a wide range of plants and animals.

This is a very different image to the one we have had of a European landscape dominated by dark primeval forests. When these grazing animals were domesticated or hunted to extinction, we forgot the crucial function they played in our ecosystem, and so, we tend to imagine our wild landscape to be an undifferentiated expanse of tree cover.

Central to this theory is the important role of “keystone species”, the large animals who roamed the open pastures, and in the process of their exploring, hunting and grazing, contributed most to the spread of biodiversity and the maintenance of complex interconnected ecosystems.

Vera put his theories to the test when he became the brains behind

Oostvaardersplassen, a Dutch project of rewilding on reclaimed land. Now referred to as the ‘Dutch Serengeti’ due to the distinctive chirping of rare meadow birds, Vera rewilded the area by first allowing nature to take its course on the land, before introducing large grazing animals that were as close as possible to what would have roamed this land thousands of years ago: heck cattle, Konik horses, red deer.

Vera’s project faced significant controversy and was heavily protested when it became apparent that part of this ‘natural’ ecosystem would be an annual mass die-off of these big herbivores. In the early Holocene period as Vera imagines it, there would have been lots of native predators like wolves to keep a natural check on these herbivores. Now, they face the much more ignoble death of slow starvation.

The winter of 2017-18 was a particularly bleak time on the plains of Holland: the number of animals

fell from 5,200 to 1,850, with most being put out of their misery with a bullet before starvation could finish them. Finally, the outrage became so great that the provincial government stepped in to manage the project.

Back in England, the couple take a similar approach to Vera: they introduce pig species that are as close as possible to wild boar; longhorn cattle, which approximate their ancestor, the aurochs; and exmoor ponies which are closest to wild horses. The role of roaming herbivores in transforming the landscape becomes apparent, cattle hoofprints become vibrant ecosystems teaming with insect life, pigs “rooting” through soil rapidly restores it to health, providing new opportunities for seeds to germinate.

Subscribe

The rapid increase in the diversity of wildflowers and vegetation brings back rare species of everything from butterflies to birds. The Knepp estate becomes the only area in Britain where the endangered turtledove is increasing its numbers. More exotic animals like storks and beavers are reintroduced. Apparent stumbling blocks to the ambitious project, like the spread of destructive thistle, are dealt with naturally: a huge flock of butterflies from Africa lay their eggs in the outbreak of “cursed thistle”, and it never returns again.

The end result is a thriving, wild and gorgeous natural landscape. Once the natural state of Western Europe, but something most of us will never see.

I’ve thought a lot lately about how barren our landscape is. I am from a country known for its natural beauty and luscious green landscapes, but there is a depressing realisation that even here, we encounter nothing that is really “wild”.

In fact, Ireland is a relatively barren place, gutted of much of its natural beauty in recent centuries. The 16th and 17th centuries were particularly brutal on Irish forestry. As large areas of land were transferred to British settlers, they set about deforestation for crops and livestock, and for timber to supply their navy.

By the end of the 19th century, less than 1% of Ireland’s original forests remained.

Trees had always been central to Irish culture. Much of pre-Christian, Brehon law dealt specifically with trees, and there were harsh penalties and fines for damaging or cutting down our native trees. For example, cutting down an oak or a hazel tree would put you on the hook for two and a half cows.

An Irish ballad titled ‘Caoineadh Cill Chais’, or ‘Lament for Kilcash’, captured the despair of a native at seeing the massive ecological destruction of the 16th century. Here is the translation of the opening verses:

Now what will we do for timber,

With the last of the woods laid low?

There’s no talk of Cill Chais or its household

And its bell will be struck no more.

That dwelling where lived the good lady

Most honoured and joyous of women

Earls made their way over wave there

And the sweet Mass once was said.

Ducks’ voices nor geese do I hear there,

Nor the eagle’s cry over the bay,

Nor even the bees at their labour

Bringing honey and wax to us all.

No birdsong there, sweet and delightful,

As we watch the sun go down,

Nor cuckoo on top of the branches

Settling the world to rest.

A mist on the boughs is descending

Neither daylight nor sun can clear.

A stain from the sky is descending

And the waters receding away.

No hazel nor holly nor berry

But boulders and bare stone heaps,

Not a branch in our neighbourly haggard,

and the game all scattered and gone.

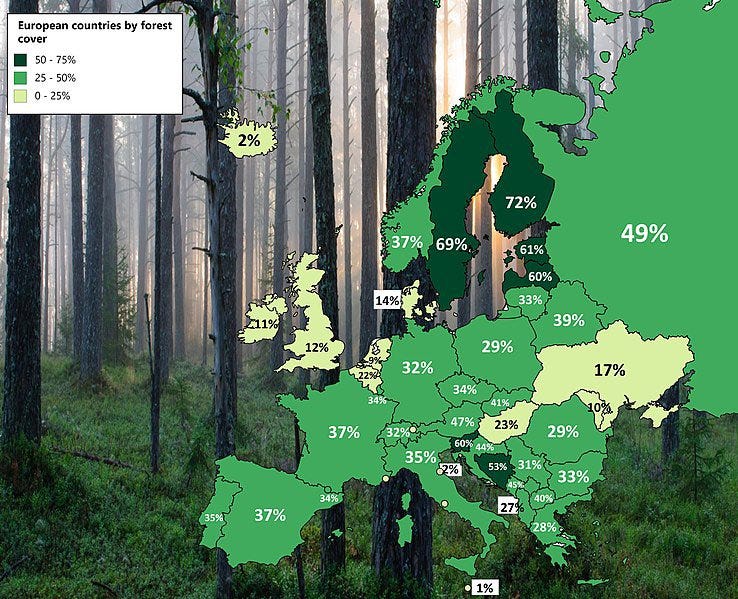

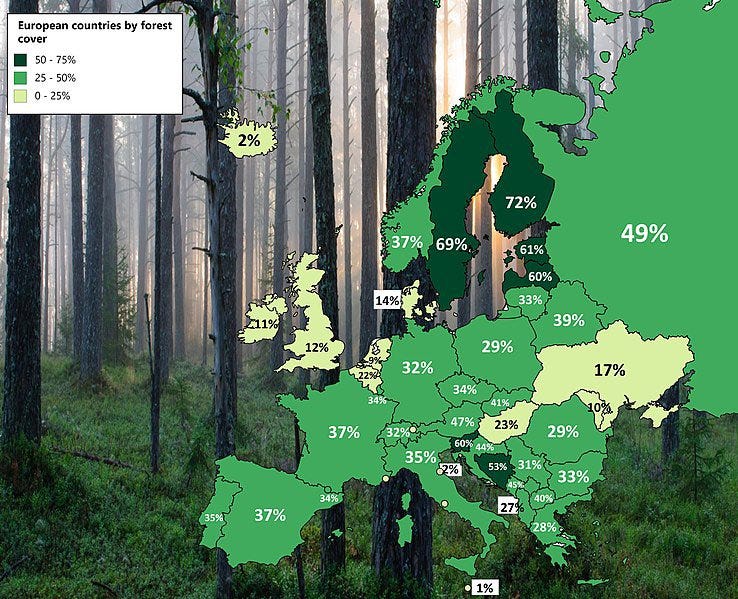

Apocalyptic. Yet sadly, reforesting or rewilding Ireland was never a project taken up by Irish nationalism after independence from the crown. Ireland remains one of the least forested countries in Europe. Nominally, 11% of the country is covered with forest, but most of that is grown commercially by farmers for timber and carbon sequestration. There is no attempt at restoring a real ecosystem, just the production of trees en masse in industrial conifer plantations. Only 2% of Ireland is covered with our wild, native broadleaf trees.

In a demonstration of what little regard the government planners of reforestation have for the native ecosystem, the most prominent tree in commercial forestry today is the foreign Sitka Spruce, originating from North America. Over 230,000 hectares of invasive Sitka spruce have been planted in Ireland, accounting for half the trees in the country, under an initiative by the government’s commercial forestry body.

Most of this is planted in our native, biodiverse peatland. This is “marginal” land, too boggy and not quite suitable for modern agriculture, but just good enough to be covered in American evergreens. Only, this marginal land would be wonderfully biodiverse if left to itself. These smothering phalanxes of trees shut out birds, including now endangered species like curlews and hen harriers.

Sitka spruce is non-native and it feels out of place in our landscape. It doesn’t become part of a thriving forestry ecosystem; it is chosen because it is fast-growing, easy, and productive for the timber industry. In Heideggerian terms, these conifer plantations are forestry as pure standing-reserve.

Imagine instead, if the Irish government had paid farmers on the wildlife-friendly, but commercially unproductive marginal land to rewild it, protect the natural habitat. Native trees could have been brought back, aiding the endangered birds and other species adapted to our native habitat. Much of this peatland is better at fulfilling modern government’s targets of carbon sequestering than the industrial timber plantations anyway. And these areas could have become tourism hubs and inspired similar initiatives in Europe.

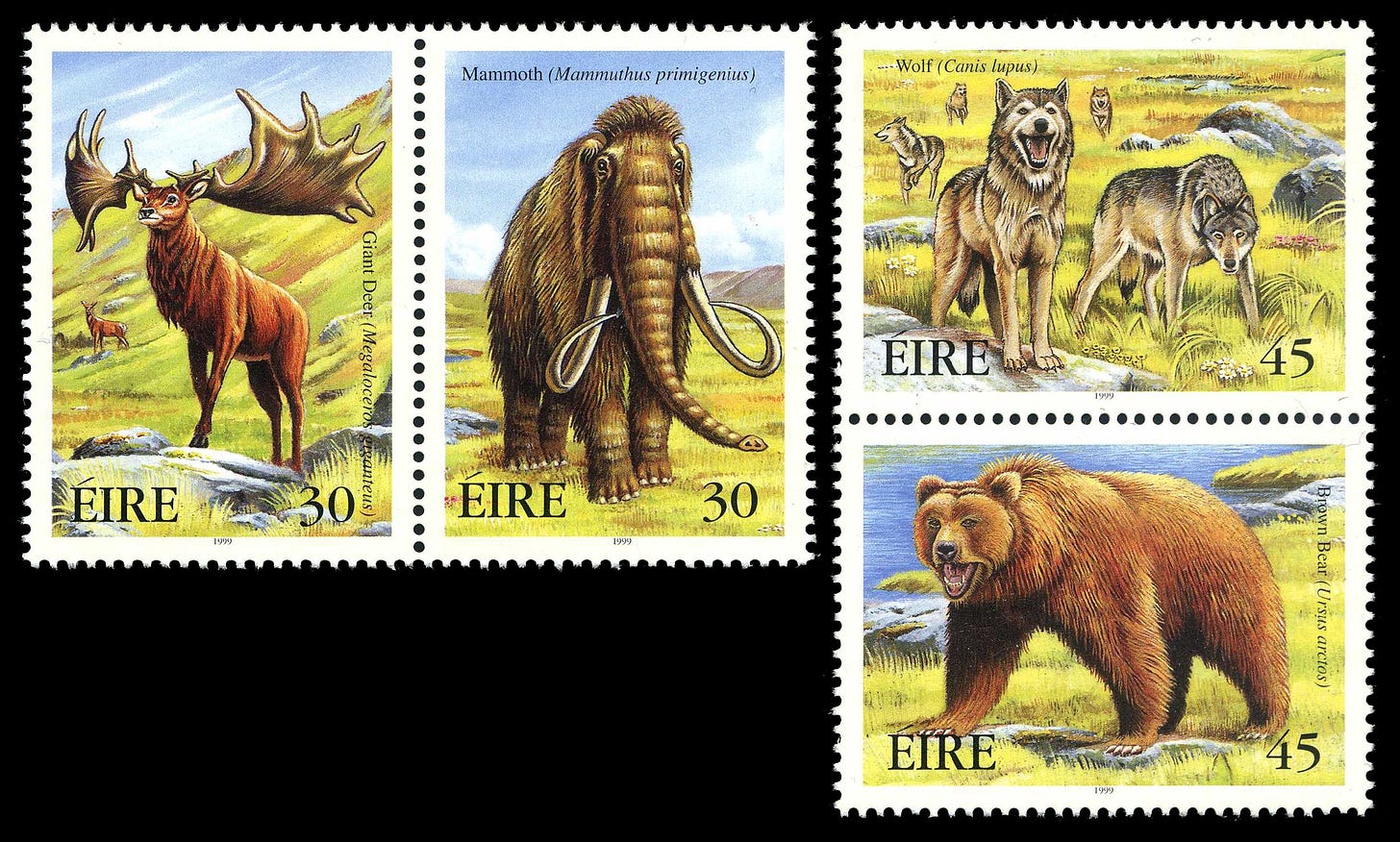

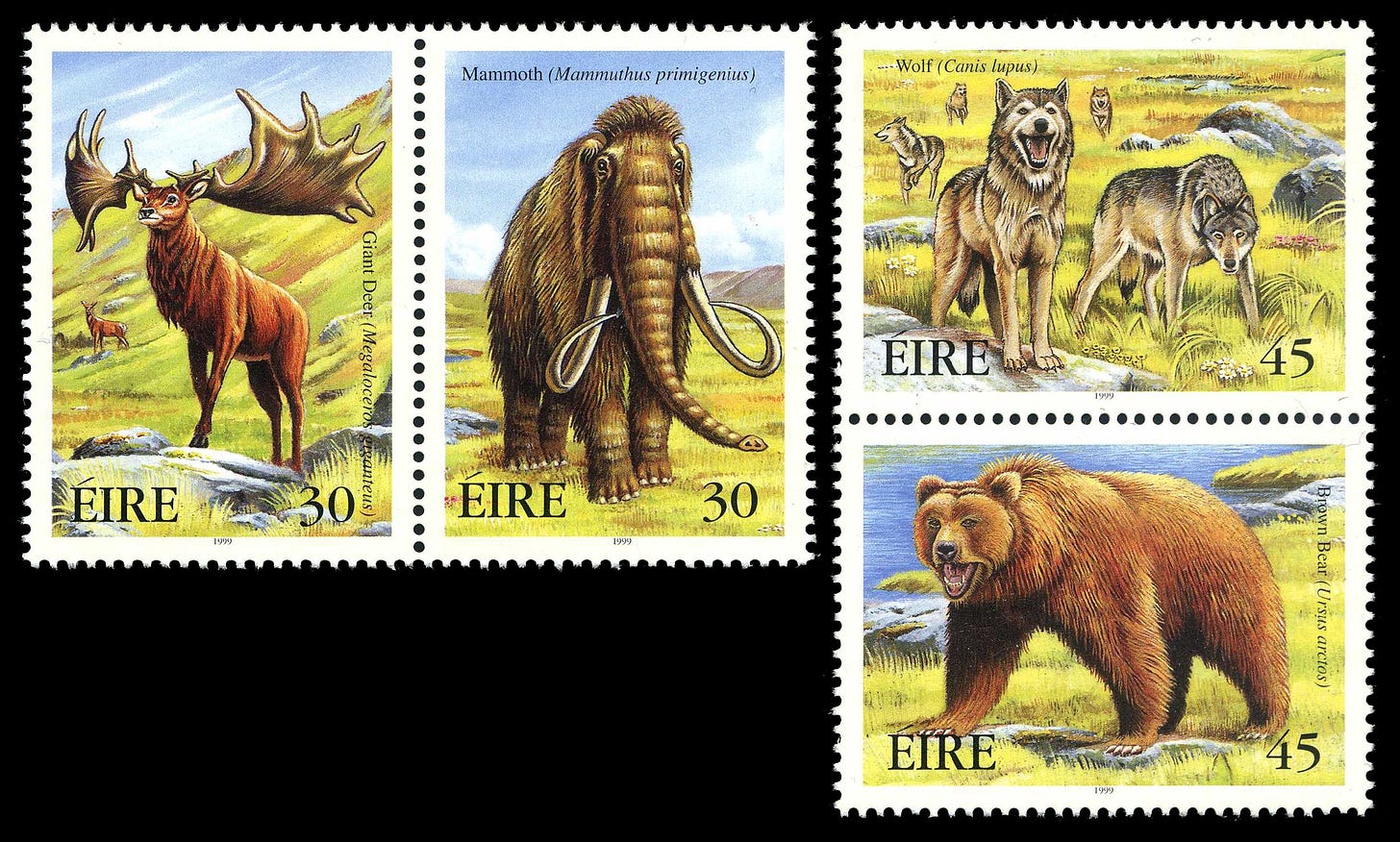

Ireland's loss of forestry goes hand in hand with the substantial loss of animal species in recent history.

Grey wolves roamed Ireland as recently as the 18th Century, before English lords targeted the troublesome hunters for extermination. Around the same time, the gorgeous European wildcat was wiped out in Ireland due to deforestation.

Subscribe

Large, flightless birds called Great Auks, similar to penguins, once roamed Ireland’s coastlines, before they were hunted to extinction to use their feathers for pillows around the 16th century.

Wild boars and bears used to roam Ireland, and many ancient texts make special note of the abundance of boar on the island. This was a food source for the wolf population, but hunting boar was also an important part of Gaelic culture: a young apprentice to the warrior band of the Fianna could become a full member if he single-handedly hunted a wild boar.

Pine martens are another animal that used to be common throughout the country. They still exist in Ireland today, but are extremely rare, brought to near extinction in the 20th century due to hunting, deforestation and targeting due to them sometimes preying on livestock.

We can scarcely imagine the sight our distant ancestors encountered when they settled this island 12,000 years ago. One of the most forested areas in the world, with vast woodlands and semi-open wood pastures filled with native plants and trees: ash, elm, pine, oak, and hazel.

Grazing on these pastures would have been reindeer, the ancestors of today’s red deer, and the majestic Irish elk. Roaming amongst these large grazers in abundance would be pine martens, red squirrels, wildcats, wolves and foxes. The sound of birdsong from the island’s various bird species would be a constant accompaniment throughout the day. The few areas where our native woodland remains today are only an approximation of this environment, now emptied of their megafauna.

I have been thinking a lot about our natural landscape at the same time as I am taking a fresh look at some of the great thinkers of Irish nationalism. I’ve realised nationalism as conceived by these men was about more than mere sovereignty; it was seen as a much loftier attempt to restore a uniquely Irish high culture of heroism. It looked hopefully to the flowering of a natural aristocracy. In this, our relation with wildness and nature’s law is central.

To be an ethnonationalist is to see some irreducible value in the unique forms of the natural world, and this extends from the natural world to the safeguarding of the unique world-sense of a people.

We will never get to see a truly “wild” Ireland, or any other European country, but I think a reasonable goal for any nationalist movement would be leaving a good portion of its land unspoiled.

There are already exciting rewilding projects happening across Europe: in the Iberian highlands, wild horses roam their natural steppe habitat, with scavenger birds and the Iberian lynx being brought back to their place a the top of the food chain; in the Affric highlands of Scotland, bare hillsides worn out from overgrazing are being transformed into wild forest occupied by deer and restoring the iconic Scottish wildcat; after 200 years of absence, European bison are returning to Romania’s wild Southern Carpathians; and wild Elk are beginning to populate the 450,000-hectare Oder Delta on the Polish-German border.

Population decline and the emptying of rural areas in Europe presents challenges, but also opportunities.

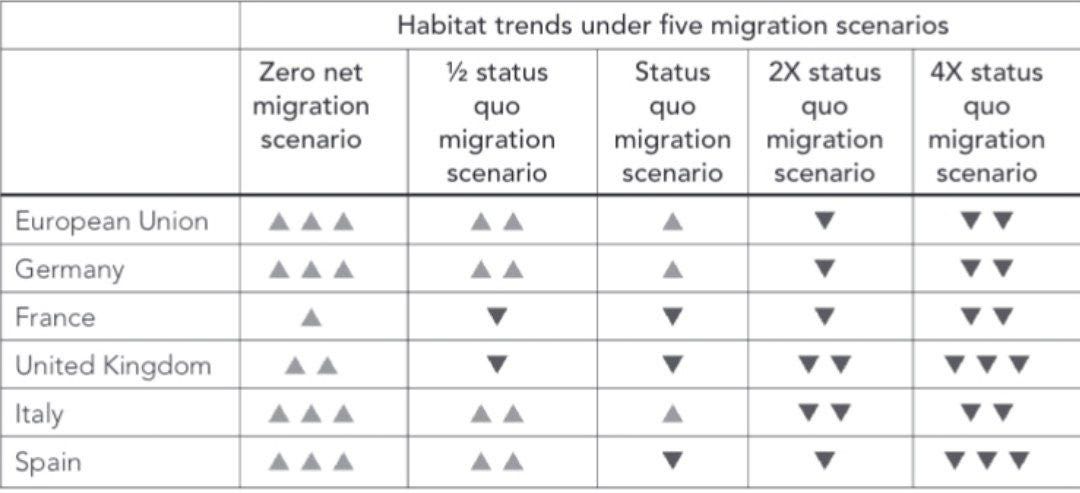

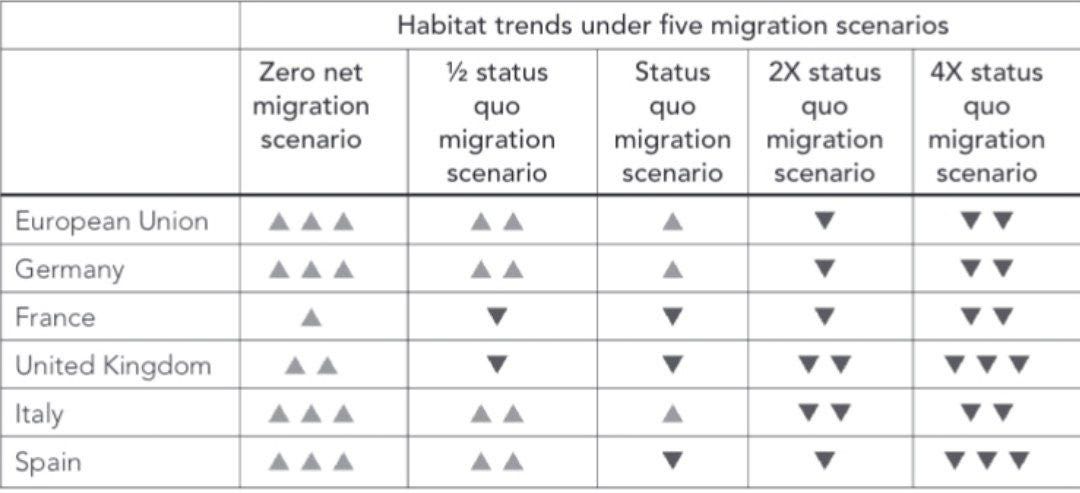

A 2019 study on

the potential environmental impacts of EU immigration policy laid out the impacts on the European habitat on a number of potential approaches to immigration policy. In all countries studied, the most optimal approach was one of zero net migration, with scenarios envisioning greater rates of immigration than we currently experience leading to substantial loss of European biodiversity.

As the authors note:

Reducing immigration can help create ecologically sustainable societies that share the landscape generously with other species, while increasing immigration will tend to move EU nations further away from these goals.

One straightforward policy implication, based on the EU’s strong environmental commitments, might be that European nations with high immigration levels, like Germany, Spain and the United Kingdom, should reduce them.

Allowing some rural areas to rewild could also create new tourism and other economic opportunities for young European farmers who are already heavily reliant on EU grants. International bodies like the EU already pour billions into environmental projects aimed at reducing carbon which could be redirected to rewilding.

Despite the overwhelming evidence of the negative effects on immigration-driven population expansion on the European habitat, establishment political parties in Europe remain committed to mass-immigration in most EU countries, and typically, popular green parties embrace it even more readily.

So it must fall to the true ecological vision offered by the right to chart an alternative course for Europe. Instead of pursuing the endless growth mindset of our current technocrat social planners, this century can be one of correction for Europe, where, after two centuries of industrialisation, explosive population growth, and overuse of soil, we finally let our native land breathe again.