During the fiery, obstinate struggles of the reactionary forces with those of the revolution, in which both reaction and revolution overlooked the arrival of a new common foe—Communism—there appeared on the political horizon of Russia phantoms which one would think could be born only in the imagination of the creator of the Apocalypse.

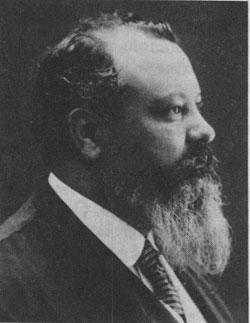

One of the first was the former horse-thief, drunkard and profligate, Grishka Rasputin. The very name of Rasputin, which means "profligate," seemed, however, to contradict the part which the mysterious adventurer played and with the by-names which he soon acquired, such as "the holy old man," "spiritual father," "wonder-worker," "giver of bliss," etc.

An illiterate peasant from the province of Tobolsk, a habitual drunkard, Rasputin engaged with a band of gipsies in horse-stealing, and was many a time pursued by the peasants and police. At last one day, after an unsuccessful expedition, he was nearly captured, but escaping at the last moment, he hid in a secluded monastery, whose Prior was the severe ascetic, but psychically abnormal Pimen.

While in the monastery Brother Gregor learnt a little curing and writing, but was not admitted to priesthood because of his lack of all education, and also because of his unrestrained habits.

Veritable legends were told of the romantic excursions Rasputin undertook into the neighbouring villages, of his success with women, and of his genius in addressing different people in a different and most impressive manner.

When the Prior Pimen felt the need of monetary succour he usually sent Rasputin to the rich and Godfearing Tobolsk and Tartar merchants. Rasputin always knew how to persuade them into munificence, and this made the profligate "little brother" highly esteemed with the claustral community, who employed him as their diplomatic envoy to the world without.

However, stories of Grishka's ebriety, gambling, and profligacy arrived from all quarters. People spoke of unheard-of orgies arranged by the "little brother" after every successful diplomatic enterprise for money for the monastery; people spoke of his share in the bold incursions of burglars beyond the Urals.

One day the news came that during one of his love excursions in a village a fight ensued, and that Grishka knifed one of the peasants. After this he did not return to the monastery, but in the disguise of a monk wandered a long time in Siberia, till he reached the Volga. Here he soon acquired fame as a "saint," "God's man," among the elderly women devotees of the rich merchant class.

Of course, it was impossible to deny that this man possessed some extraordinary powers, his wild, catlike, glowing eyes seemed to pierce into the brains of men, to enter into their very souls.

He could size up every man at the first glance. He had an intuitive insight into human beings, their characters, psychology, and desires. Besides, he was a powerful hypnotiser, had an irresistible power of suggestion, and exercised his influence equally upon individual persons as upon great assemblies. He had the force of authority and conviction in his voice, a dull-sounding, threatening voice resembling the gloomy murmur of a virgin Siberian forest, in which he spent his romantic and stormy youth.

I remember boarding a tramcar in Petersburg. It was early in the morning, and there were only few people about. I was immersed in my newspaper, when all of a sudden I felt almost physically something like a strange blow on my head. I looked up quickly, and I met the eyes of a tall, lean man with an ascetic, immovable face. He was richly dressed in a magnificent sable fur coat and cap, but the fashion of his dress was strange, and looked like a cassock. I was at a loss as to his identity, seeing that he had top-boots, and under the fur coat I noticed, when he opened it to draw out a handkerchief, an ordinary Russian shirt of red silk. Again I felt compelled to look into the eyes of the strange man. Suddenly I noticed with a beating heart that those eyes vanished, and in their stead crossed and shot forth radiant beams, concealing his eyes and a part of his face.

Suddenly his eyes appeared again, and round his lips played a disdainful, scoffing smile. I understood that he tested his hypnotic power on me. I decided not to look at him any more, and I succeeded in my resolve. Leaving the car, I had to pass the stranger. He touched my arm and said:

"I know you're a journalist. And you don't want to look at me? Why? I am Rasputin, Gregor Rasputin, the 'man of God.'"

Such was my first encounter. The second was semimystical. There was an exhibition at the Academy of Fine Arts in Petersburg, where crowds were thronging and pressing in front of a sad, unfinished picture of the well-known Russian painter, Nicolai Rayevski. The picture represented the portrait of a tall, lean man in a black, semi-ecclesiastical habit, a thin, emaciated face, with long black hair falling down the forehead, and a dishevelled black beard. The picture was marked in the catalogue: "No. 144. The Portrait of an Unknown Man."

But the attention of the crowd was riveted, not by the habit, the face and the black hair, not even by the undefined mysteriousness of the portrait. One and all were looking into the black, piercing eyes, vivid and watchful, like the eyes of an animal preparing for a sudden and dangerous assault. When in turn I looked, approaching the portrait, the eyes vanished behind the radiant veil which emerged from the mysterious black profundity of those piercing pupils.

"It's not a man, it's the devil," said someone among the spectators.

"It's Rasputin!" explained another. "What do you want?"

"The impure power," whispered a pious lady.

"The powerful, holy man of God!" protested immediately several voices.

The crowd dispersed. New visitors took their place.

My third encounter with Rasputin was amidst fatal circumstances.

A reporter of the paper which I edited telephoned through to me that Rasputin had been killed, and that the authorities were searching for his body. After a few hours I learned that the body was found. I went to the spot at once. Just before I arrived the corpse was lifted through a hole cut In the ice on the Little Neva River. He was dressed in a magnificent fur coat and a black silk shirt; on one leg I noticed a high jute snow-shoe upon a patent leather boot His head was bare. His face was smashed, one eye injured, and his throat bore signs of strangling fingers. He was the victim of political, perhaps personal vengeance, sprung on him by the Grand Duke Dimitri, Count Sumarokov-Elston, and the Deputy to the Duma Vladimir Purishkevich.

The artist Rayevski, who painted Rasputin—at the request of the Empress Alexandra, his portrait was removed from the exhibition on the first day—was very interested in the mysterious personality, and told me a great deal about the "man of God." It was clear from what he said that Rasputin must have exercised an irresistible charm on women. That ruthless man managed to penetrate into the boudoirs of the most distinguished titled ladies in Petersburg with the same facility with which he philandered in the modest apartments of the elderly widows of the merchant class, or with the variety stars in the Villa Rode. He could be enrapturing, fiery, overwhelming. He used often to say:

"Woman is created for the pleasure and glory of man!"

Pious people asserted that Rasputin had an unmatched talent for prayers. He said his prayers in simple, uncultured words, but with burning passion, poetry, and inspiration. It seemed as if he would behold the very face of God, to Whom he was speaking in human, simple, and comprehensible words. The nervous shivering of his shoulders, the spasmodic voice, the facial mimicry full of pain and penetrating imploration, the fire, and the tears of his eyes made a terrifying impression on the pious, mystically moved spectators. The dull, threatening voice of the old thief rose to such a power of tune, resounded with such passionate force that it seemed as if by the lips of this man somebody else, pure and full of bliss, was uttering life-saving words of Eternal Grace.

He turned from time to time towards the Holy Picture, outstretched his hands, and spoke in tones imploring and commanding:

"Turn Thine eyes upon us and give a sign that Thou hearest me!"

And the man praying seemed to perceive the eyes of the Holy Image moving and gazing upon the crowd.

Rayevski told me that one afternoon when Rasputin was sitting for his portrait, a well-known nobleman drove up in his car to the painter's studio, and rushing in, fell on his knees in front of Rasputin with the words:

"Father! My brother is dying! Help!"

Rasputin got up at once, and forgetting his fur coat, ran down the staircase murmuring:

"Lord! Oh Lord! Creator of all life, grant me to arrive in time!"

Arrived at the palace, Rasputin found an elderly man in a terrible state of asthma, which was still further endangered by a heart attack. The sick man had already lost consciousness. Rasputin looked a long time into his face, and then exclaimed, or rather howled like a terrified dog in a winter's night:

"Why dost thou not call for help to our Lord? Why dost thou not ask Him: 'Deliver me from my disease, and give me, O Creator, the strength to praise Thy name in glory?' Awake, and repeat these words of my prayer! Awake!"

"Can you imagine," said Rayevski, "the Count actually moved, opened his amazed eyes, pressed his hand to his heart, and repeated the short and not quite common prayer word for word. I was really astonished!"

Another of my Russian friends, the well-known poet and critic, A. A. Izmailov, told me his own experience once.

"I succeeded with great difficulty in getting at Rasputin; I wanted to interview him, but I was careful to tell him through the servant that I wanted to speak to him about our mutual friends from the Volga. When I entered his room he was seated in a comfortable chair. He measured me with an inquiring eye and with a forbearing smile, said:

"'A journalist! Why do you try to deceive me?'

"He stopped short I kept silent, knowing his hatred of journalists, who had annoyed him much in the past. Besides, his words had embarrassed me strongly and I could not say anything.

"'I shall not talk about any of my affairs to you,' said Rasputin after a long while, 'but I want to speak of you. Death passed over your head when you were eleven years old. I can see it plainly. Tell me how it happened.'

"Of course" related Izmailov, "when I was eleven I went with my brother to try to shoot a hare. My brother was to do the shooting and I was to do the beating. I had scarcely entered the garden-bed when I tumbled over a root and fell to the ground. This saved my life, for at the very moment the hare jumped tip; my brother fired, and the shot went over my head, which was protected by the high bed.

"When I finished my story, Rasputin said:

"'Beware of a narrow street in which stands a house of red brick and two turrets. Remember it and go now.'"

I don't know if Izmailov heeded the warning or not. I lost sight of him when he remained in Soviet Russia, and it is quite possible that he perished in its bloody whirl.

Alfred Rodé, the owner of the notorious villa, and some officers of the late Imperial Guard told me of the orgies arranged by Rasputin, of their lasciviousness, cynicism, and vulgarity. He often let himself go, offending his guests, laughing at their opinions and their manners. Once, whilst boasting of his intimate relations with the Imperial Court, he showed his richly embroidered silk shirt, and chuckling with laughter, said swaggering:

"It's Shashka's work." Shashka being the Empress's pet name.

There followed a great scandal. One of the officers jumped at the "man of God," and in the free fight which ensued wounded him with a bottle.

Rasputin was reputed to be aware of the attempts contrived against him; he escaped several of them, and he knew that a sudden end awaited him, and he lived in mortal fright. Once, in an attack of that terrible longing which befell him in the expectancy o death, while sitting at the bedside of the Empress, who, surrounded by her daughters, was writhing in pain, he called out in ecstasy:

"Not a hair of yours shall fall to the ground as long as my pictures and dress shall be with you!"

It must have been true, because about the middle of 1916, after an attempt on Rasputin, the photographer Ocup received the order to call on him and to make seven large portraits of the "Old Man"—the Tsar's family consisted of seven members—to perform all the operations in the presence of Rasputin's secretary to whom the plates were also to be handed over.

At the same time news spread from the Tsarskoye Selo Palace which amazed everybody. One learnt that after a long conversation with the Empress and her daughters, Rasputin left the apartments of Alexandra in tears, and went into his room, where he changed his dress, to return afterwards carrying his black silk shirt torn into seven pieces.

His power rested upon mysticism, the exploitation of momentary moods, forebodings of an impending debacle, and the skilful handling of situations as they arose.

In Siberia, where Grishka was hated, to-day already, during the Bolshevist regime, people whisper:

"Rasputin was a dog, but. a strong, supernatural man. He foretold the Emperor Nicholas's black days that should follow his own death, and so it happened. He foretold that the Romanovs would live as long as they should have with them his pictures and bits of his shirt—and they lived until the Commissar Yurovsky took all this away from them, when they were murdered. Strong, uncanny was Grishka! Antichrist! The servant of the devil!"

Several attempts were made on Rasputin's life, but without success. Two of them were most dangerous. One in Siberia, when the monk, Heliodor, sent a half-demented peasant woman, who inflicted several wounds on him with her knife. The wounds were rather serious, but Rasputin lived.

Another time, when he travelled in sledges from Petersburg to Tsarskoye Selo together with Madame Wyrubova, the Empress's lady-in-waiting, the sledges were upset by an unknown motor-car, which succeeded in effecting its escape. Madame Wyrubova was seriously hurt, but Rasputin only slightly bruised.

At the head of the organisation which combated Rasputin were the Moscow Metropolitan Makar, the Bishop of Samara Pimen, and the monk Heliodor, supported by a band of influential and rich men belonging to the Nationalist circles.

After the last and successful attempt on the life of the spiritual director, the despondency of the Empress and her daughters was limitless. They even went into mourning for him. The body was buried in a magnificent chapel erected for the purpose In the Park of Tsarskoye Selo. Daily pilgrimages of the Tsar's family to the "Old Man's" grave proved the genuine and profound sorrow for the "holy father," whose life was so mysteriously bound up with the fate of the dynasty.

Speaking of the mysterious ties which existed between the Romanov dynasty and Gregor Rasputin, I remember a legend which was very popular in old Moscow and particularly alive during the war of 1812, after Napoleon's conquest of the Kremlin.

When the Romanov dynasty, in the person of the youthful Tsar Nicolai Teodorovich, was elected to the Russian throne, the solemnity was held in the Ipatiev Monastery, built by the Ipatiev, a rich family of traders in Kostroma. During the procession one of the epileptics of the name Grishka became mad and started to shout prognostications:

"The house of Romanovs will reign long centuries over us. It will attain glory and power. It will perish tinder the Ipatiev roof after 'Grishka'!"

The history of the dynasty corresponds with this augury, which was at first incomprehensible to its contemporaries.

The dynasty reigned for more than three hundred years, achieved glory and power, and perished after Grishka (Rasputin) under the roof of the Ipatiev's in Yekaterinburg, where the descendants of the founders of the Ipatiev Monastery were removed from Kostroma.

In 1812 there appeared in Moscow a "prophet" Grishka, who foretold the fall of Russia and the Imperial dynasty. It was then that people remembered the legend, all the more as Russian troops retreated in the presence of the Tsar in part towards Kostroma. The Police Commissioner of Moscow, hearing of Grishka's prophecies, had him captured and flogged to death.

Grishka's prophecy of a "God's man" and "epileptic," pronounced two centuries earlier, were revived for more than a hundred years, only to become true in a more terrible and sinister manner after Grishka, a "God's man" according to the beliefs of the Court and some Russian aristocrats of the twentieth century.

en.wikisource.org