This is a thread to explore and discuss the emerging global usage of energy weapons and the psychological, physiological, and biological effects caused by such devices and technology.

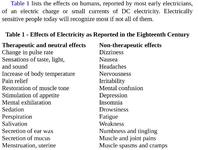

I will begin with this piece of relevant literature, a book called "The Invisible Rainbow" that explores the entirety of the evolution of "medicine" in the west from the 1800s until the present, and how electricity and technological leaps have simultaneously changed the biological front.

Here is the pdf for reading, though I recommend buying a hard copy if you like this as it will be interesting to share with others around you.

https://archive.org/details/the-invisible-rainbow

Here is the Prologue:

"Once upon a time, the rainbow visible in the sky after a storm represented all the colors that were. Our earth was designed that way. We have a blanket of air above us that absorbs the higher ultraviolets, together with all of the X-rays and gamma rays from space. Most of the longer waves, that we use today for radio communication, were once absent as well. Or rather, they were there in infinitesimal amounts. They came to us from the sun and stars but with energies that were a trillion times weaker than the light that also came from the heavens. So weak were the cosmic radio waves that they would have been invisible, and so life never developed organs that could see them.

The even longer waves, the low-frequency pulsations given off by lightning, are also invisible. When lightning flashes, it momentarily fills the air with them, but they are almost gone in an instant; their echo, reverberating around the world, is roughly ten billion times weaker than the light from the sun. We never evolved organs to see this either.

But our bodies know that those colors are there. The energy of our cells whispering in the radio frequency range is infinitesimal but necessary for life. Every thought, every movement that we make surrounds us with low frequency pulsations, whispers that were first detected in 1875 and are also necessary for life. The electricity that we use today, the substance that we send through wires and broadcast through the air without a thought, was identified around 1700 as a property of life. Only later did scientists learn to extract it and make it move inanimate objects, ignoring—because they could not see—its effects on the living world. It surrounds us today, in all of its colors, at intensities that rival the light from the sun, but we still cannot see it because it was not present at life’s birth.

We live today with a number of devastating diseases that do not belong here, whose origin we do not know, whose presence we take for granted and no longer question. What it feels like to be without them is a state of vitality that we have completely forgotten.

" Anxiety disorder," afflicting one-sixth of humanity, did not exist before the 1860s, when telegraph wires first encircled the earth. No hint of it appears in the medical literature before 1866.

Influenza, in its present form, was invented in 1889, along with alternating current. It is with us always, like a familiar guest—so familiar that we have forgotten that it wasn't always so. Many of the doctors who were flooded with the disease in 1889 had never seen a case before.

Prior to the 1860s, diabetes was so rare that few doctors saw more than one or two cases during their lifetime. It, too, has changed its character: diabetics were once skeletally thin. Obese people never developed the disease.

Heart disease at that time was the twenty-fifth most common illness, behind accidental drowning. It was an illness of infants and old people. It was extraordinary for anyone else to have a diseased heart.

Cancer was also exceedingly rare. Even tobacco smoking, in non-electrified times, did not cause lung cancer.

These are the diseases of civilization, that we have also inflicted on our animal and plant neighbors, diseases that we lie with because of a refusal to recognize the force that we have harnessed for what it is. The 60-cycle current in our house wiring, the ultrasonic frequencies in our computers, the radio waves in our television, the microwaves in our cell phones, these are only distortions of the invisible rainbow that runs through our veins and makes us alive. But we have forgotten. It is time we remember."

In addition to this beginning piece, I will add the interviews of one Barry Trower, a British physicist and formerly of the Royal Navy, who was pioneering much of this tech in the mid-20th century. Mind control is not as conspiratorial as it sounds, its more like strategic mind influence with guaranteed results. Read this article, and watch some of his interview videos below:

"Barrie Trower “The Cooking of Humanity ”Microwaves, Smart Meters and the use of electronics for “mind control” *UPDATED*"

https://www.fcc.gov/ecfs/document/1030855353584/5

"Mind control , Neuro weapons. Dr. Barry Trower interview." He starts talking around 5:55

"Remote Influencing Technologies, DEWs. Interview with Dr. Barry Trower."

"Effects of Microwaves - Barry Trower - even before 5G"

Take what you will from this, but this is the more existential threat to all of us with the current psychopaths in charge than anything else.

I will begin with this piece of relevant literature, a book called "The Invisible Rainbow" that explores the entirety of the evolution of "medicine" in the west from the 1800s until the present, and how electricity and technological leaps have simultaneously changed the biological front.

Here is the pdf for reading, though I recommend buying a hard copy if you like this as it will be interesting to share with others around you.

https://archive.org/details/the-invisible-rainbow

Here is the Prologue:

"Once upon a time, the rainbow visible in the sky after a storm represented all the colors that were. Our earth was designed that way. We have a blanket of air above us that absorbs the higher ultraviolets, together with all of the X-rays and gamma rays from space. Most of the longer waves, that we use today for radio communication, were once absent as well. Or rather, they were there in infinitesimal amounts. They came to us from the sun and stars but with energies that were a trillion times weaker than the light that also came from the heavens. So weak were the cosmic radio waves that they would have been invisible, and so life never developed organs that could see them.

The even longer waves, the low-frequency pulsations given off by lightning, are also invisible. When lightning flashes, it momentarily fills the air with them, but they are almost gone in an instant; their echo, reverberating around the world, is roughly ten billion times weaker than the light from the sun. We never evolved organs to see this either.

But our bodies know that those colors are there. The energy of our cells whispering in the radio frequency range is infinitesimal but necessary for life. Every thought, every movement that we make surrounds us with low frequency pulsations, whispers that were first detected in 1875 and are also necessary for life. The electricity that we use today, the substance that we send through wires and broadcast through the air without a thought, was identified around 1700 as a property of life. Only later did scientists learn to extract it and make it move inanimate objects, ignoring—because they could not see—its effects on the living world. It surrounds us today, in all of its colors, at intensities that rival the light from the sun, but we still cannot see it because it was not present at life’s birth.

We live today with a number of devastating diseases that do not belong here, whose origin we do not know, whose presence we take for granted and no longer question. What it feels like to be without them is a state of vitality that we have completely forgotten.

" Anxiety disorder," afflicting one-sixth of humanity, did not exist before the 1860s, when telegraph wires first encircled the earth. No hint of it appears in the medical literature before 1866.

Influenza, in its present form, was invented in 1889, along with alternating current. It is with us always, like a familiar guest—so familiar that we have forgotten that it wasn't always so. Many of the doctors who were flooded with the disease in 1889 had never seen a case before.

Prior to the 1860s, diabetes was so rare that few doctors saw more than one or two cases during their lifetime. It, too, has changed its character: diabetics were once skeletally thin. Obese people never developed the disease.

Heart disease at that time was the twenty-fifth most common illness, behind accidental drowning. It was an illness of infants and old people. It was extraordinary for anyone else to have a diseased heart.

Cancer was also exceedingly rare. Even tobacco smoking, in non-electrified times, did not cause lung cancer.

These are the diseases of civilization, that we have also inflicted on our animal and plant neighbors, diseases that we lie with because of a refusal to recognize the force that we have harnessed for what it is. The 60-cycle current in our house wiring, the ultrasonic frequencies in our computers, the radio waves in our television, the microwaves in our cell phones, these are only distortions of the invisible rainbow that runs through our veins and makes us alive. But we have forgotten. It is time we remember."

In addition to this beginning piece, I will add the interviews of one Barry Trower, a British physicist and formerly of the Royal Navy, who was pioneering much of this tech in the mid-20th century. Mind control is not as conspiratorial as it sounds, its more like strategic mind influence with guaranteed results. Read this article, and watch some of his interview videos below:

"Barrie Trower “The Cooking of Humanity ”Microwaves, Smart Meters and the use of electronics for “mind control” *UPDATED*"

https://www.fcc.gov/ecfs/document/1030855353584/5

"Mind control , Neuro weapons. Dr. Barry Trower interview." He starts talking around 5:55

"Remote Influencing Technologies, DEWs. Interview with Dr. Barry Trower."

"Effects of Microwaves - Barry Trower - even before 5G"

Take what you will from this, but this is the more existential threat to all of us with the current psychopaths in charge than anything else.